The full power of a Gibbons carving comes from seeing it in situ. So, why go see Gibbons’ work in a museum? Because that’s where the sought-after object is. And by going to the V&A Museum we can see several of Gibbons’ works over a span of time and a variety of media. London’s Victoria and Albert Museum holds 2.3 million objects. Let’s go see 5 of them, in timeline order.

Picture Surround – Cassiobury Park – circa 1675-1677

We see a lot of “overdoor” and “overmantel” carvings as we seek out Gibbons’ work. These are names given to a set of three carvings that typically surround a picture and are positioned as their names state, over doors or over mantels. Each set of three includes a horizontal crest or swag and two vertical “chains” or “drops.” The format was well established by the time Gibbons started producing them. Until he came along, most overmantel carvings depicted tightly packed garlands of flowers, and sometimes fruit, and maybe ribbons, and were carved as high relief objects, several inches thick.

Gibbons adopted the form and immediately began enhancing it. He added foliage, vegetables and many other things such as fish, sea shells, dead game, putti, musical instruments, baskets, drapery folds, and heraldic shields mixed in with the flowers and fruit. He set his work apart from others by enhancing the depth of “high relief.” By heavy undercutting, piercing, and layering, his compositions take on an airy realism. He honed these techniques to a level unmatched then and very rarely matched since.

We also see that Gibbons used symmetry only loosely for many years. His predecessors and peers were quite formal in matching symmetry, some making the vertical drops almost mirror images of each other. Gibbons, on the other hand, is almost a “symmetry contrarian.” Vertical drops keep almost the same masses and almost the same lengths from side to side, but rarely very similar layouts.

This particular picture surround was originally carved for Arthur Capel, the Earl of Essex. The carving was part of a commission that included overdoors, overmantels, panels, borders, and frames that decorated ten rooms of Capel’s manor house in Cassiobury Park, near Watford, Hertfordshire. It is thought to have been an overdoor in the house’s great dining room. For those following personal connections, Arthur Capel was acquainted with John Evelyn, the person who “discovered” Gibbons. The architect for the house was Hugh May, another person who knew Gibbons.

The cornice shown in these pictures was not carved by Gibbons, but is present to support the cresting piece. The carved pictures inside the surround are not Gibbons’ work either. The original manor house no longer exists, but the V&A was fortunate enough to acquire this relatively early example of Gibbons’ overdoor/overmantel work.

The work is about 82 inches (208 cm) wide and nearly the same height.

An aside: Some time ago, I pursued some questions regarding the splitting in the cartouche. David Esterly kindly pointed me to the conservator, David Luard, who had worked with this carving before it was installed at the V&A. Mr. Luard offered a few interesting comments:

However this carving is largely an amalgamation of pieces (by Gibbons) and the whole carving is made up of about 90 pieces instead of the 7 or 8 that one would expect. For instance there is a large section in the right hand drop that should be horizontal but is now vertical.

The carving was painted and varnished when at Cassiobury and it was stripped at some point after removal, probably with caustic soda, which has distorted the wood somewhat.

Not a carving to trust when looking at Gibbons’s design techniques.

David Luard, Luard Conservation

You can find it on the Level 6, in the Furniture gallery, Room 133. Here is the V&A Catalog entry.

High relief – The Stoning of Saint Stephen – circa 1680-1710

The story goes that John Evelyn, a writer and member of high society, walked by Gibbons’ workshop in Deptford and saw through a window that Gibbons was working on a marvellous carving of the Crucifixion. Evelyn arranged for the carving to be shown to King Charles II and his Queen, but it was ultimately rejected because the times were shunning images of Christ, the saints, and most anything appearing to be Catholic. This leads us to believe that Gibbons gave up religious subjects (other than hundreds of angelic putti) and turned to other work.

Upon his death, Gibbons’ high relief carving depicting the Stoning of Saint Stephen was found among his possessions. From that, we learn he had not completely abandoned religious subjects. There are no letters, receipts or other documentation about this carving. We don’t know why he carved it, other than perhaps for personal satisfaction. Likewise, we don’t know when he carved it. The V&A Museum attributes it to a very long and vague 30 year period.

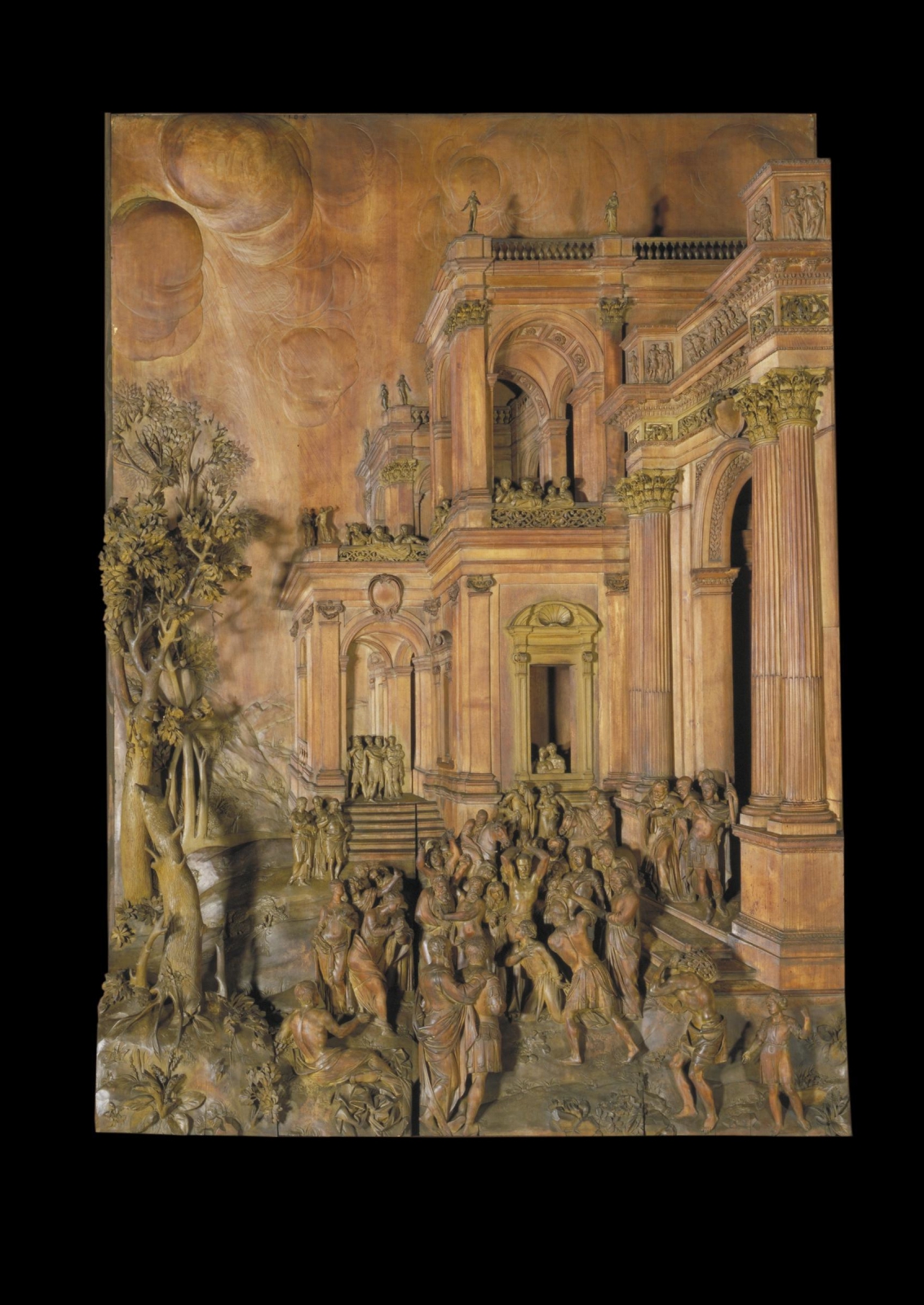

When I found this carving, I was stunned by its size. Yes, we can read in books the fine print annotations such as “72 1/2 x 52 3/4 inches,” but does that really sink in? That’s 6 feet tall and over 4 feet wide.

Until visiting the museum, all I had ever seen of this carving is the image at the right. It’s the only image available online and in numerous books. Now, how deep does that image look? It’s a straight on shot and we can’t tell. Discovering the depth was the most stunning aspect of seeing this carving. I have a folded paper tape measure in my wallet, but was so awed by this carving that I forgot to measure the actual depth. It must be between 15 and 18 inches deep. Imagine: from the cluster of people in the center of the scene to that group standing on the stairs in the background is 10 to 12 inches. The trees standing to the left are almost completely independent of the background. The building in the background (viewed from above, if we could) is “L” shaped, protruding 2-3 inches from the back and side walls of the carving, and much more where the corner extends next to the stairs.

Three hundred years, and careful conservation, have been good to this carving. Yes, we can see a split in the middle, but the rest of the joins are still intact. In his book, “Grinling Gibbons and the Art of Carving” (published by V&A), David Esterly shows a diagram of the carving made up of 13 major boards and a few smaller insets.

Consider the extent of the work. Dozens of human figures at different perspective sizes, trees and plant life, a building with columns, capitals, friezes, railings and other ornaments, and statues atop the building. On thinking about carving all of it, there is no longer any wonder about it being so large.

One of the reasons we usually see only that particular picture of the carving is due to how the carving is displayed. It is in the corner of a room, inside a glass case, and not brightly lit. My attempts to photograph it, both with and without flash, produced terrible results. The image we see above was clearly taken professionally, in good lighting, and most likely without the glass case and all the reflections from light and windows.

Despite the dim lighting, reflections on the glass case from ceiling lamps, and my camera’s flash, I offer a few photos below solely to show the remarkable way foreshortening is used to create the illusion depth. Note also how the varying sizes of the human characters add to the illusion of depth. The people in the extreme foreground are about 6 inches tall, the ones on the stair landing and balcony only about 4, and the ones atop the uppermost railing maybe only 2-3 inches tall. Lastly, one side view shows some underlying structure, a notched block that is about 8 long (back to front).

You can find it on the Level 2, British Galleries, Room 54b. Here is the V&A Catalog entry.

Two marble altarpieces – The Putti with Shields – circa 1686

Art history and attribution is difficult without good documentation, and in many cases, there is very little documentation. There were few newspapers in the late 1600s and almost certainly no art magazines. Much of what historians know is from sifting through letters, mercantile receipts, license records, and property transfer records. Some of what I read tells of Gibbons possibly having an apprenticeship in the Netherlands under Artus Quellin I, and his cousin Artus Quellin II. The cousins operated “the premier” sculpture workshops in the Netherlands. Later, the son of Artus II, Arnold Quellin, had a “foreign servant” license arrangement with Gibbons. Details of whether the apprenticeship led to Arnold’s emigration to London and employment by Gibbons are unknown, but historians today often question the marble works credited to Gibbons while Arnold Quellin was apparently in his employ.

The V&A credits these two marble pieces to: “Probably by Arnold Quellin and Grinling Gibbons.” They were most likely part of an altar arrangement in Whitehall Palace.

You can find them on the Level 1, Sculpture Gallery, Room 24. The V&A Catalog entries are here and here.

In the round – Point Cravat – circa 1690

“Point Lace” cravats were the height of fine fashion around Europe in the late 1600s. They were of Venetian origin, almost certainly from the island of Burano, where handmade lace can still be found today. Art historians have not yet found clear documentation of why Gibbons carved this piece. The best speculation is that it was to display his virtuosity to potential patrons.

We do know that some years later it was owned by the art critic and writer, Horace Walpole, who so admired Gibbons that he had a room in his Strawberry Hill home decorated with Gibbons’ work. Walpole is reputed to have actually worn the cravat to a party he had at his home in 1769. Look closely and you’ll find that a few loops around the bottom are broken off. We don’t know if they were broken from Walpole’s handling or in the 300 years the piece has existed.

This is another object I found inside a glass case. While there was good light and no unwanted reflections, focus is a bit softer than I would have liked. Yet, the detail is incredible.

Talk about a way to sell one’s ability!

You can find it on the Level 2, British Galleries, Room 118a. Here is the V&A Catalog entry.

Bonus: Lace Brooch – Cravat – 1980 – Arline Fisch

In the category of “inspired by,” we find an amazing knitted lace cravat that looks very much like the carved point lace cravat. A textile and jewelery artist, Arline Fisch, likes to explore non-traditional materials. She made a Gibbons inspired cravat / ascot / brooch by knitting it from silver wire. Can’t you hear those needles clicking! 🙂

It is similar in size to Gibbons’ cravat, looks very much like it, and is displayed in the museum’s Jewellery room. Find it on the Level 3, Room 91.

This particular piece of work is in a room that disallows photography, and the Catalog image is “in copyright,” not available for download. See it here.

Oh, by the way…

The Victoria and Albert Museum gets its name from the royal support of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who in 1899 ceremonially laid the cornerstone of the present building. It is a fabulous institution, catering to decorative arts and design in every medium imaginable. It claims ownership of 2.3 million objects. Its superb online catalog has over 1.7 million entries. By the way, this is the best online museum catalog I’ve had the pleasure of using. Those links included with each object above are to that catalog. And for those who judge the quality of a museum by its gift shop, this one will be at the top of your list. The gift shop is beautiful, large and so very full of temptations. The café too is far better than most.

Important: If you go… Do your own research first. Know what you are looking for and use the catalog to locate the pieces. It works! The museum’s own website advises exactly the same. Do your own research first. The staff can’t possibly know about everything in their collections and where any particular object is located.

… even if those objects are 15 foot tall stone statues standing on the outside of the building. 🙂 An incredibly friendly gentleman at the central information desk has a name badge that’s worn enough to indicate he’s not a new hire. He was unaware of the 32 statues of painters, architects, sculptors, and craft workers that stand on the Exhibition Road and Cromwell Road facades of the building. OK, they’re up high and I imagine our info desk person takes the tube to work and comes in through the underground entrance under Exhibition Road and never actually studies the outside of the building. Do your own research!

Getting there: On a pleasant day, walk a few blocks down Exhibition Road from Hyde Park or the Globe Theater. On a rainy day, take the tube to the South Kensington station and look for the tunnel, a walk of about 200 rain free yards to the museum entrance. Throughout London’s Underground network, there are many designated areas where “buskers” set up and play their favorite repertoires. This tunnel has a busker area. The day we visited, a performer was playing blues music New Orleans style.

A note of appreciation: The V&A was founded under a mandate of making its collections freely available. The majority of the museum is open without entry fee. Only special shows, obviously costly to produce, have fees. Beyond this, the museum welcomes personal photography, even considerate use of flash photography. And lastly, for many of its own images the museum has a generous license agreement for non-commercial use. The museum’s generosity makes it easy for me to bring you these pictures of Gibbons’ work.

Thank you for sharing these photographs and for the handy tips!

It’s my great pleasure Cheryl. I’m pleased you enjoyed them.