This is “the big one,” in terms of how many photos I can bring you. Hampton Court Palace is one of the British museums that allows photography for non-commercial use. I tried to capture everything that my simple camera could reach, missed only one pair of carvings, and got most of them relatively sharp. This is a very long article, and by itself, will increase the number of photos of Gibbons’ carvings on the Internet.

Hampton Court Palace was originally built for Henry VIII in the 16th century. Our interest is a large addition made in the late 17th century for King William III and Queen Mary II. These are the rooms that Gibbons decorated (1699 – 1701).

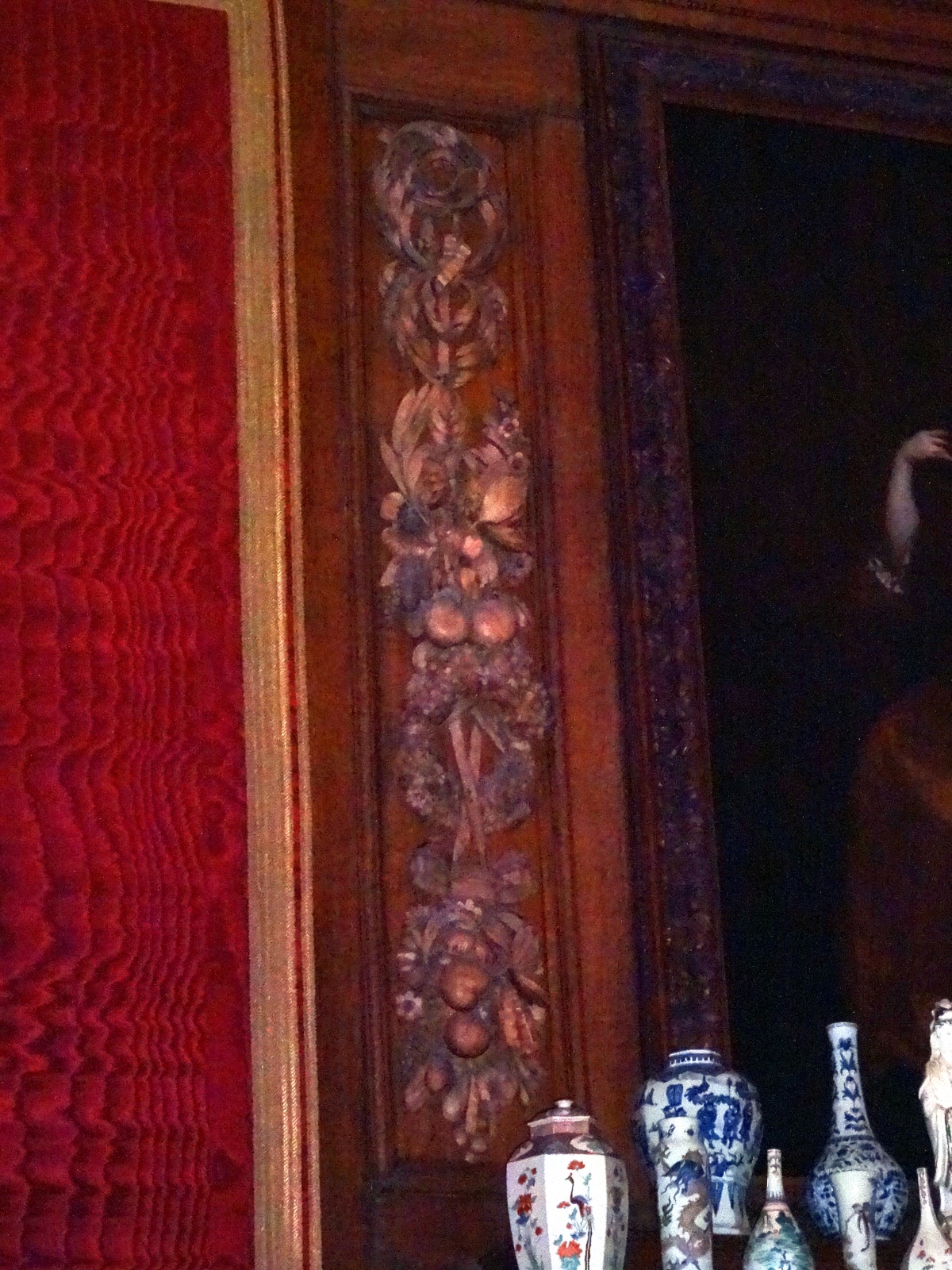

Let’s go for a walk through William’s rooms. Carvings in the four main rooms follow a set arrangement. We pass through the rooms from west to east. Over each west doorway is a painting, flanked on either side by vertical “drop” carvings. Each of the main rooms has a fireplace and large mantel, with a prominent overmantel painting. These paintings are surrounded by either two-piece or three-piece surrounds. We leave each room through the east doorway, above which is also a painting, flanked by carvings. Each room also contains beautiful tapestries, but since I was singularly focused on carvings, you see only small fragments of those tapestries. …and at the end of the article, you’ll discover the tapestries are indeed highly valued.

For each room, I start with a quote of part of the information provided on an information card in that room.

The King’s Presence Chamber

“High-ranking people would be allowed into the King’s presence by the Gentleman Usher at the door.”

Upon entering this room, turn around and look up to find the west overdoor painting and carvings. The drops beside the overdoor paintings measure about 7 feet. The painting is “Classical Ruins” by Lucas Achtschellinick.

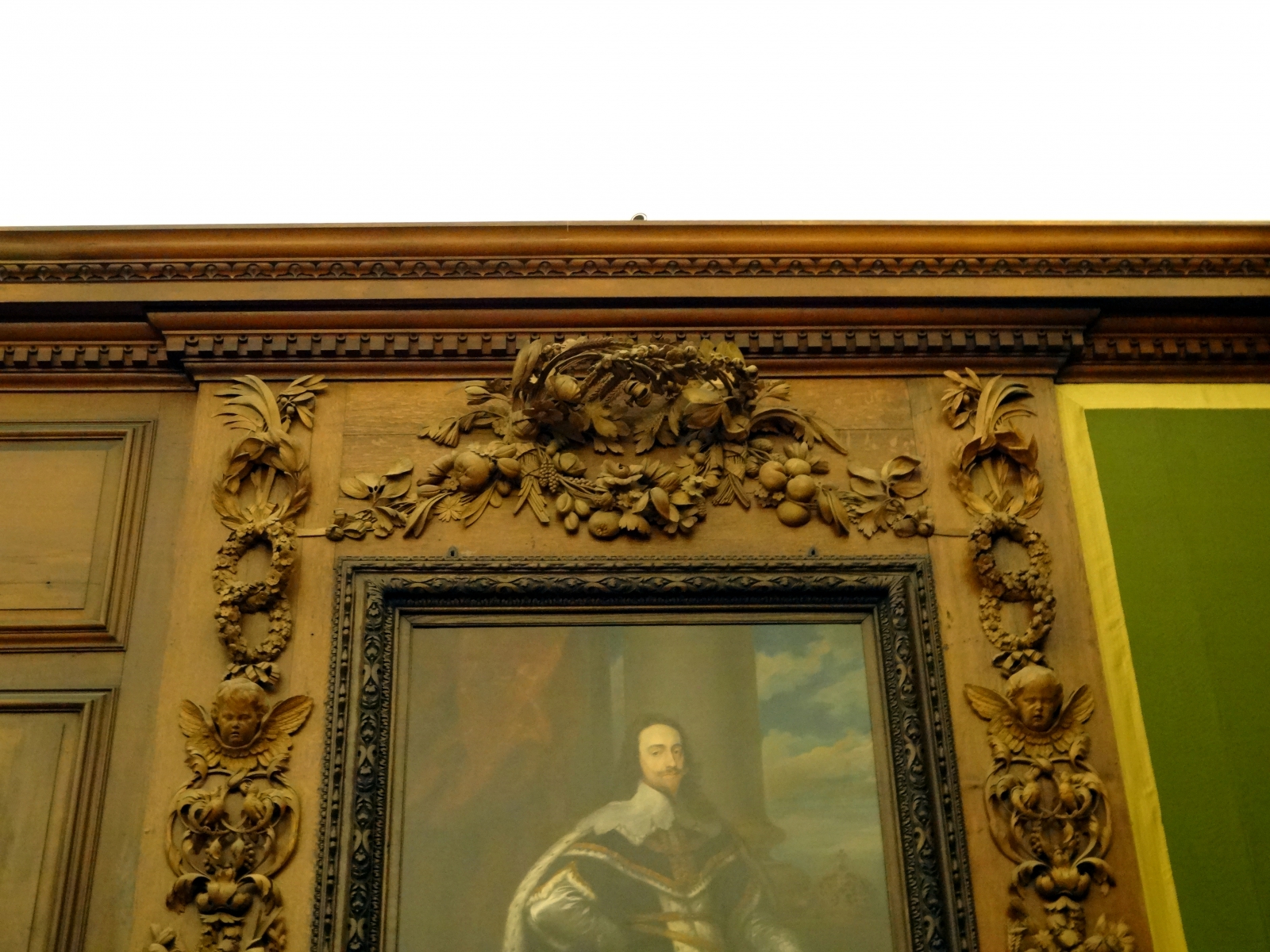

The overmantel in this room is a two-piece surround, having only the vertical drops. There is no cresting piece. The painting is “James Hamilton, 2nd Marquess of Hamilton” by Daniël Mijtens.

The east overdoor painting and drops. The painting is “Classical Landscape” by Jean-Jaques Rousseau.

The King’s Eating Room

“The King was expected to dine here on occasions in front of ‘persons of good fashion and good appearance,’ in order to display the sumptuousness of his food and to reassure everyone that he was in good health.”

The west overdoor painting and drops. The painting is “Building with Figurines” by Jean-Jaques Rousseau.

Notice the sheaves of wheat in the cresting of the over mantel surround, signifying abundance and good health. The drops offer us good studies for linenfold draperies. I took some extra detail pictures of the drops to show overall depth of the objects and the thinness of edges of the draperies and leaves. Even in that photo with soft focus the thinness of the leaves is obvious.

Without getting out my tape measure, I estimate some of these objects to be 6 to 8 inches deep. Esterly tells us, from first hand experience of handling the carvings, that some of these were built up in layers that are nailed together.

The painting is “Christian IV of Denmark” by Karel van Mander III.

The east overdoor painting and drops. The painting is (another) “Building with Figurines” by Jean-Jaques Rousseau.

The King’s Privy Chamber

“By William III’s time, the Privy Chamber was no longer very ‘privy,’ or private. He had decreed that all ambassadorial visits, the most formal of occasions, should take place in this room.”

On March 31, 1986 a fire broke out in an apartment above William’s rooms. It smoldered for many hours before finally breaking through the ceiling of the Cartoon Gallery, a room on the other side of the long wall of the Privy Chamber. As the smoldering progressed, people rushed into William’s rooms to save any art objects not nailed down. Yes, as you have guessed, the Gibbons carvings were all nailed in place high above the rescuer’s heads and could not be removed. The ceiling broke and many of these rooms were quickly engulfed by the fire. However, while many carvings suffered damage, luckily only one was completely lost. See a section below, “David Esterly’s Restoration,” to learn more about recreating and restoring the carvings.

The west overdoor painting and drops. The painting is “Classical Landscape” by Hendrick Danckerts.

Here again, I could get close enough to the overmantel to get more detail pictures. See how the putti differ. The painting is “Queen Elizabeth Bohemian” by Gerrit Van Honthorst.

The east overdoor painting and drops. The painting is (another) “Classical Landscape” by Hendrick Danckerts.

The King’s Withdrawing Room

“This smaller room was a more informal space where the King and his ministers and courtiers could withdraw to meet and do business.”

This is the room where I missed taking pictures of two carvings. I missed the carvings over the east doorway.

It’s a shame because the two overdoor paintings are interesting. Both are of victors holding the heads of the vanquished. Over the west doorway is “Judith with the head of Holofernes” by Guido Reni. Over the east doorway is “David with the head of Goliath” by Domenico Fetti. It was mentioned on one of the information cards that William himself selected the artwork for these rooms. Since this was the room where the king and his ministers got down to business, I wonder it these particular overdoor paintings were intended as advice to the people doing business.

The west overdoor painting and drops. The carving to the right of the painting over the west doorway is the one that was completely destroyed in the 1986 fire and replaced by David Esterly. There’s more on Esterly’s restoration further down the page. The painting is “Judith with the Head of Holofernes” by Guido Reni.

The crest on this overmantel is deeper than others, and we have yet 2 more different putti. The painting “Charles I” by Anthony van Dyck.

The King’s Great Bedchamber

“The most splendid room in the State Apartments was the final destination for the most privileged visitors. With extraordinary informality, courtiers were admitted to see the King as he prepared for the day.”

This room is indeed the most ornate, including expansive tapestries, a Gibbons carved frieze moulding surrounding the room, and a lavish painted ceiling bounded by gold plated moulding. William III had the artist Antonio Verrio paint the ceiling with the mythological story of Diana, the moon goddess.

The lighting in this room was very subdued, apparently to give a more intimate feel, and my camera barely found enough light for photos. I have quite a group of dark very fuzzy pictures from this room. Here are the best for you.

The overmantel painting is “Anne Hyde, Duchess of York” by Sir Peter Lely.

David Esterly’s Restoration

David Esterly tells of his fiancé taking him to see Gibbons’ carvings at St. James Piccadilly long ago. That was a life changing moment, one that began his transformation from academic to woodcarver. He has long been today’s leading expert on Gibbons and is superbly accomplished at carving as Gibbons carved. He imitates, not copies, and has built his own very impressive repertoire of floral carving. In one of his books, “The Lost Carving: A Journey to the Heart of Making,” Esterly tells of being in his upstate New York workshop on March 31, 1986 and hearing news from London about a raging fire at Hampton Court Palace. Esterly had extensively studied Gibbons’ work there and was well known for his expertise. It wasn’t long before the phone started ringing, bringing requests for him to come to the palace, survey the damage, and help determine what to do next. In “The Lost Carving,” Esterly tells of spending a year at Hampton Court, of replacing a carving that was totally destroyed, of helping make repairs to others, and of battling with people of several royal agencies about how the carvings are displayed: white as he believed Gibbons intended or brown as the Victorians saw all wood.

“The professional beast within me stirred. If a Gibbons piece was going to be replaced, then somebody would have to replace it. Who? Surely not I, who’d always flaunted my abhorrence of anything that smacked of reproduction.

Surely not I? The beast opened its yellow eyes and bared its teeth.

Surely nobody but me.”

– David Esterly, “The Lost Carving: A Journey to the Heart of Making“

As Esterly wrote his book, the reference photos available to him showed this carving positioned to the left of the west overdoor painting. After all the restoration work was done, some of the carvings and paintings ended up in different places. Today, the lost carving is to the right of the west overdoor painting.

Notice how Esterly’s own photo shows a white limewood carving, while the carving mounted in the room is stained (or waxed?) brown like all the others. Esterly has always been at odds with Palace authorities who want to have Gibbons’ work appear brown. Esterly is convinced that Gibbons preferred his limewood carvings be left white. Esterly failed at persuading the authorities at Hampton Court to restore the carvings to white, or at least display his replacement carving unstained. Asked in an NPR interview (at 6:03) if he was satisfied with the way his completed work was mounted, Esterly answered, “No, I was not happy. I didn’t go out of my way to see it.”

Another Gibbons carving – Chapel Royal

At the far northwest corner of the palace buildings, you can find a stunningly beautiful chapel. It is ornate, with extensive carvings, brightly painted byzantine style ceiling, and a reredos carved by Gibbons in 1699. Alas, no photography is allowed in the chapel.

Oh, by the way…

Conversations with the warder

There are gentlemen in long red coats, called warders, who help visitors and answer our questions. While in the Kings Guard Room, which has no carvings, I was discussing with the warder the spectacular display of weapons; pistols, long guns, knives, swords, all displayed in great circles high on the walls. I mused that it might be interesting to display our shotguns that way.

Later we discussed the 1986 fire and speculated about which carving “the gentleman from New York” replaced. During that conversation, the warder mentioned that all of the tapestries (huge tapestries, some as large as 20 feet on a side) are now mounted with velcro. The first thing for warders to do in case of fire is to get visitors out of the palace. The second is to rip down the tapestries and get them out, then all the other art objects. However, the carvings are still nailed to the walls high above the reach of rescuers.

The largest and possibly oldest grape vine

Serving fresh fruit to your visitors was something only royalty could afford in the 18th century. Hampton Court has a grape vine that was started in 1768 for King George III (yeah, Americans, that one!), and has been kept flourishing since. Until the 1920s the grapes were so highly prized that the vine was guarded and the bunches numbered and accounted for. The sweet black grapes are sold today (in season) in the gift shop.

These days, the vine’s care is entrusted to gardener, Gillian Cox, who regularly offers a talk about the origin, history, and upkeep of the great vine.

Lastly, Esterly’s sandpaper discovery

I hate sanding. A lot of woodcarvers also hate sanding. Yet, high-finish woodcarvings need to be smoothed. There was no 3M or Norton in the 1680s, nor any other kind of manufactured sandpaper. What did Gibbons and his carvers use? This was an area Esterly explored in great depth while restoring the fire damaged carvings. He found traces of extremely fine parallel scratches on smooth surfaces. What made them? You’ll find the answer in “The Lost Carving.” Hint: it is organic material, something that grows from land, not from the sea.

Hi Bob, just a couple of comments.

The overmantle carvings in the Presence Chamber are by John Le Sage – yes someone else snuck in – not a very well known carver who became a silversmith, registering a hallmark in the 1720s.

The other point, as the conservator who carried out most of the work, is that I had absolutely no issue with lightening the carvings, in fact, with Esterly, promoted the idea. It was the Palace authorities who were against it

Thank You Mr. Luard!

All corrections, or additional information, are welcome.

It is interesting to learn of John Le Sage. Several times I wondered why that overmantle did not include a top piece. A different artist might be the explanation. Thanks.

As I look at what I wrote about the stained carvings and review how Esterly described the situation in his books, I believe I need to change the “curators and conservators” phrase to “Palace authorities.” Will do shortly. Thanks for clarifying your point of view and offering yet more knowledge.