The King David panel has come home. It disappeared for about 300 years and is now safely home.

“Home” is the Fairfax House, a stately Georgian town house in York, UK. The Fairfax House acquired the King David panel in the fall of 2017 and is featuring it in an exhibit beginning 14 April, 2018.

Gibbons arrived in Britain 350 years ago and spent his early years in York. We don’t know much about his work while there, but history now brings us this remarkable panel from that time. The carving has apparently been in private collections for most of its life. Its origin is estimated as about 1670. One wonders where it was for nearly 300 years. It first emerged into the art world’s awareness in a 1963 auction at Sothebys in London. From there, it was in the private collection of Cyril Humphries, a London art dealer, who sold his collection in 1995, via Sothebys which had by that time moved to New York. The next known owner was A. Alfred Taubman, another private collector, and coincidentally the owner of Sotheby’s NY. Mr. Taubman passed away in 2015 and his private collection was sold in 2016. The King David panel was purchased by the art collectors, Tomasso Brothers, and brought back to Leeds, UK, just down the road from York. It appeared in 2016, once again available for sale, and in danger of being sold again to someone abroad.

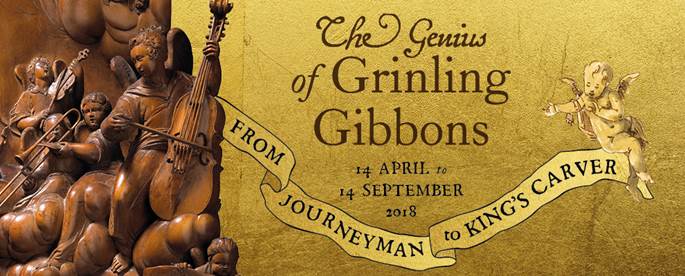

The people at Fairfax House recognized an opportunity to not only bring the panel closer to where it was created, but also to make it available publicly instead of being yet again hidden away in a private collection. They mounted a very challenging fund raising campaign and completed the purchase in October 2017. I learned of this wonderful news when Dr. Sarah Burnage, a curator at Fairfax House, contacted me late in 2017 about using one of my Gibbons photos for their exhibit guide. The exhibit, “The Genius of Grinling Gibbons, From Journeyman to King’s Carver,” opened at Fairfax House 14 April 2018, the 370th anniversary of Gibbons’ birth, and ran through 14 September 2018. While no longer the featured exhibit, you can see the panel anytime at Fairfax House.

The King David panel is notable in a number of ways. First, it is the only known survivor of Gibbons’ early work in York. Second, as with his “Crucifixion” panel and the “Stoning of Saint Stevens” panel, Gibbons worked from artwork of others, transforming two dimensional engravings into three dimensional deep relief carvings. Third, the skill of execution is remarkable for such a young artist.

The artwork that inspired Gibbons was an engraving by Johann Sadeler, produced 1589-1593. The engraving was a derivative of a yet earlier painting by the Flemish-born painter, Peter Candid. The scene is titled “Performance of a Motet of Orlando di Lasso.” It shows King David playing a harp and singing, surrounded by other instrumentalists and dancing cherubs. The scene is associated with the biblical Psalm 148, “Praise the Lord.” About a century later (before or after Gibbons carved the panel, we don’t know) the image from the engraving was painted on glass for two prominent families in York, the Barwicks and the Fairfaxes.

Art historians attribute this panel to Gibbons, not only from the style of carving, but also from the back-to-back GG ligature carved into the side of the organ case. This was a signature device that Gibbons used on other carvings of that time. Historians also surmise that this piece was commissioned by the Barwick family, because Gibbons changed the cartouche at the top of the harp from what is seen in the engraving to a representation of the coat of arms of the Barwick family.

Remarkable to me is the very small scale of the piece. Having stood before the “Stoning of Saint Stevens” panel, which is six feet tall, I was amazed when first learning that this panel measures a mere 14 1/2 inches by 9 1/2 inches, 365mm x 237mm. Gibbons packed a tremendous amount of detail into a small space, which is exactly the same size as Sadeler’s engraving. Part of the success of these details is due to Gibbons’ use of boxwood, instead of limewood (basswood in the U.S.) which he used in much of his later work. Boxwood has grain that is much finer than limewood and is also much harder. These traits make possible the tiny details, such as individual strings of the harp and cello, the cello’s bow, the horn that is sticking out in the air. Light can be seen behind one of the sheets of music, indicating they are very thin. These tiny objects are difficult to carve at this scale, and boxwood is certainly a factor in making them possible.

There is one notable difference between the engraving and the carving. The engraving shows a complete circle of cherubs dancing around King David. The foreground cherubs are missing from the carved panel. Perhaps they were once there. If you have the opportunity to see the carving “up close and personal,” look closely at the foreground. There are several blemished areas where some dancing cherubs might have been some time ago.

The King David panel is impressive in many ways. If you can get there, visit Fairfax House to see the earliest survivor of Gibbons’ fantastic work.

A very special THANK YOU to Sarah Burnage and Fairfax House for the use of their images and exhibition guide material. Thanks also to Richard Doughty for the picture of Hannah Phillip holding the panel.

What is the music shown

What a great question Bob!

In an article at Fairfax House, Hannah Philip tells us more about the panel, mentioning that it was copied from an earlier painting by Peter Candid, which was titled “The Performance of a Motet of Orlando di Lasso.” Follow that fact a bit further along and discover that the complete motets by Orlando di Lasso numbers 500, currently published in 21 volumes. I’ll leave it to you to figure out which one it is. 🙂